种树的牧羊人 L'homme qui plantait des arbres(1988)

又名: The Man Who Planted Trees / 种树人

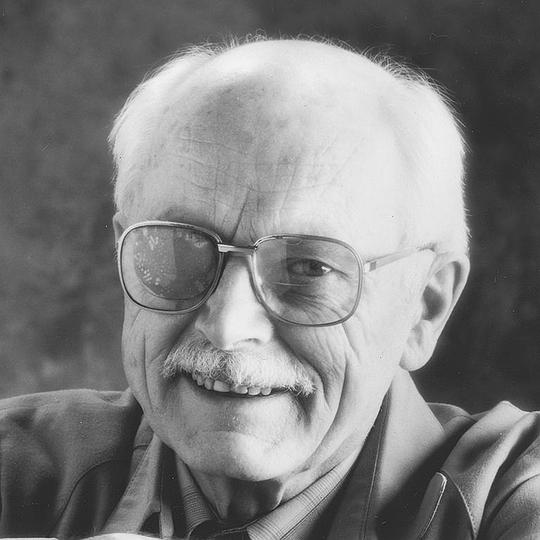

导演: 弗雷德里克·贝克

主演: Philippe Noiret Christopher Plummer

制片国家/地区: 加拿大

上映日期: 1988-06-11

片长: 30分钟 IMDb: tt0093488 豆瓣评分:9.1 下载地址:迅雷下载

简介:

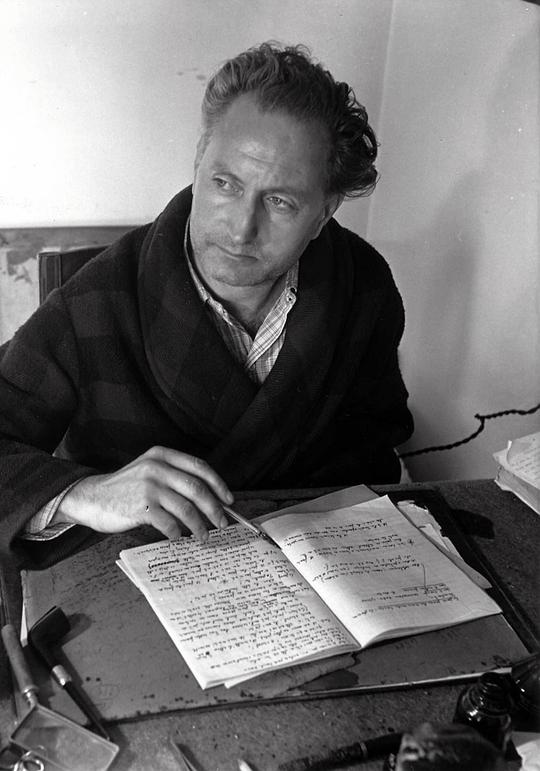

- 一个孤独的牧羊人凭着一己之力和数十年的时间,在荒漠中种出了大片的树林,把土丘变成了绿洲。《种树的牧羊人》是Frédéric BACK先生1987年出品的一部代表作品,动画的剧本改变自法国作家Jean Giono在1953年出版的同名小说。整部动画片充满了诗意的叙述。与其说这是一个动画片,不如说它是一个精致的散文。淡泊而又意味深长,风格简约而又意味深长。叙事代替了色彩和形式成为主角。

演员:

影评:

- (文选自《出发点》)

这是一部令我眼前一亮的作品。不光是因为我本身从事动画业,就算我走的不是这一行,它在我看来依旧非常出色。我认为这是一部力道十足且相当成熟的作品。费德利克.贝克本身的深度和他的创作动机,思想等,融合的恰到好处。更另我感动的是,在这个人人为未来惶恐不安的年代里,还能看到象书中人物这样的人,更是一种激励。

片中的这位普罗旺斯爷爷仿佛是一位隐居乡间的哲人,充满了成熟的睿智,让我们不由得产生强烈的憧憬。作者能用自己的表现方式使其创作动机成形,这一点另我深深佩服。

而同样令我钦佩的,还有加拿大广播电台的那群人,因为他们竟然愿意为一部看似不卖座的影片投下资金。我记得那是一个魁北克的广播电台。在加拿大各省里就属这个州是法国区,偶尔还会为独立与否争论不已。这部作品的背景是普罗旺斯,也是南法民族主义色彩浓厚的地区。因此,虽然不是很清楚,但二者之间或许有关联也说不定。

初见这部作品时,我还不了解故事背景在何处,知道是普罗旺斯之后才恍然大悟--本作品的原著小说,和普罗旺斯当地的文艺复兴运动及方言写作运动。应该有某种关系才是。

以前,我曾有过在普罗旺斯开车的经验。那里大多是绿意盎然的平原,种了很多的防风林。想来是因为季风很强的缘故。我本以为那片绿意是原生的,看了这部作品之后才明白,果然还是人为的植林。

故事里的普罗旺斯爷爷似乎是个虚构的人物,是作者汇集了许多当地人说的故事之后,才塑造出这样的人物。类似的故事在世界各地都有,日本也常常见到,特别是江户时代。

由于玉川上水被当作扑灭野火的用水,为此便在它的四周种满了树木。因为武藏野从前只是个荒凉的芒草地。八之岳山脚下的防风林,据说也是为了同样的目的而种的。

相反的例子也很多。先人在开拓北海道时种下的防风林,到了近代却因为不利于机械化而被砍掉。结果,土壤渐渐的流失掉,于是人们又说要重新种回树林。

说是自然保育,人为的成分依旧很高,我们并没有完全仰赖自然的力量去恢复旧观。其实时间可以帮我们很多的忙,只不过站在人类的立场,任自然保留原貌和人为的作用都得同时进行就是了。

日本人喜欢在神社四周维持自然林的风貌,称之为镇守之森;而为生活而种的树木则被当成一种景观。这种情况在江户时期以前还算稳定,但自从明治以后推行近代化,它们便逐渐遭到破坏。毁林,成了日本近代的历史之一。

我想加拿大应该没有这段历史,不过贝克肯定是被原著小说中种树老人的行为所感动--让荒地一步步变成绿意盎然的土地,让那里充满生命的力量,让人们在那里生活。导演亟欲表现这部作品的心情,我很能体会。

我最早接触费德利克.贝克作品是[CRAC!(摇椅)]。四.五年前,我和高畑(勲)先生因公留在美国时,在某个动画联映中看见那段短片,那部短片让我们相当震撼,我还记得在走回饭店的路上,我一边有气无力的走着,一边对高畑先生说:“我们真的不行耶!”

然后就是这部[种树的男人]。我们现在所用的赛璐珞动画很难描绘植物,光是小草迎风飘摇的景象就不容易作到生动活泼了。植物的美是在风中摇曳,在阳光下闪耀,且要在气候和光线的衬托下才显现的出来。我也曾想过自己会如何描绘它,但有一想到我们的表现手法达不到那个境界便放弃了。没想到贝克勇于正面挑战这样的主题,成果又是如此可观,光是这一点就令我佩服不已。这部作品在影像上也堪称旷世之作。

这样一部作品,当然不是一蹴而成的。要不是先有[摇椅],恐怕也不会有[种树的男人]。[摇椅]在手法上的发展,摄影师和幕后人员的心血,我想应该都传承到[种树的男人]上了,而且[种]片的工作人员应该也经手过[摇椅]才是。再者,制作群超越前作的创作意图若是不够强烈,恐怕也完成不了这样一部作品吧。

若是以同样的题材拍成写实电影,说不定反而达不到这样的震撼性。贝克在这部作品中所使用的动画手法,也不是寻常人可以套用的。而这一点正告诉我们,动画的可能性不该被含糊曲解。假使我们硬要限定动画表现的适性,势必陷入表现手法的死胡同中,因此强求其定义是没有意义的。

其实所谓的表现手法,要先有想表现的事物,再谈技术层面的问题。光有技术却没有想表现的主题,岂不是一事无成?技术原本就是为了表现事物才发展出来的方式啊。

基于这一点,我推测贝克在[摇椅]中首创的表现手法,是藉由[种]片而更臻圆满。它最好不要再往上发展,就这么维持完成的形态就很好。否则下次再有类似的创作时,将难免有旧瓶装新酒之嫌。

费德利克.贝克之所以能完成这样的作品,和他的世界观--即看这个世界的“眼神”--有很大的关系。

当我们用这样的视线去看事物时,就可以发现我们和观众的共通之处。那是一种来自深处且长期累积的人文观点。片中的普罗旺斯爷爷有一张哲学家的脸,而贝克选择这张脸的理由,我非常能了解。

种下树苗,把它养大,长成森林之后,蜜蜂也会飞来,老爷爷仿佛望着远方,看到的是往后的梦想;贝克想描绘的就是这样的观点。

我在报纸上的某个小专栏读过一篇文章,讨论日本人和欧洲人的生死观,上面说日本人老了之后渴望与自然成为一体,欧洲人则希望与自然面对面。日本人所想的与自然化为一体,感觉上象是徜徉在在绿色的怀抱中那样,可是住在戈壁沙漠里的人,应该也有他们与自然合而为一的方式。天底下又不是只有日本人想要回归自然,我想每个民族应该都有这样的想法。大自然是生命的起源,是我们了解全世界的地点,它对任何人来说都是弥足珍贵的。

费德利克.贝克出生在德法边境一个叫做亚尔萨斯的地方,但他是在加拿大才发现了大自然的可贵,也许是人们制作枫糖浆的光景触发他对故乡的思念,所以才创作了[摇椅]吧。

当全球的自然景观正一步步的被破坏,人类反而越发思慕土生土长的大地,风景,和其中的一草一木。这份思慕之情正和普罗旺斯的种树男人相通,而这也正是这部电影要传达给观众的。

我仅以一个观众的角度,写下这部作品带给我的感动。我看尤里.诺斯坦(YURI NORSTEIN)也是一样。有这些好人在,真好。 - 今天看了《种树的牧羊者》,be touched through and through。一个男子,从1914年到1947年,每年都种几万棵树,以此方式与上帝抗争,将一个满是戈壁的山丘变成了茂密的森林;将一个原是仇恨的寥落的村庄变成了一个绿柳莺啼的的地方,原来人们恨不得搬出去,现在却有许许多多的人搬进来,在那里的人是懂得享受生活,充满热情的人,而不是原先的因为憎恨而相互仇视的扭曲的村民。“原来人也是一个很伟大的东西的”。牧羊人经受早年丧子与丧妻的痛苦,他想,如果上帝让我活下来,我就每年种几万颗树,最后,种树成了他的有意义的工作,就像片中说的:“It's a perfect way to be happy”。人生中有一项值得做的事情总是好的,打个不恰当的比喻,这就让我想到了阿甘的跑步,和1900的钢琴,没有什么原因,只是愿意去想去做罢了。而当你找到了一件事,认真地做下去,一生就会变得有意义吧。

牧羊人就这样度过了一年又一年,以一只狗为伴,赶着他养的羊,晚上精挑细选出没有破裂的橡树种子,怀着永远不改变的信念。也许孤独让他少言寡语,孤独让他对外面世界的一战二战全然不知,孤独也让他比所有人都更了解他种的这片森林。他说,这片土地不是他的,但他仍然要种树。。也许隐隐之中,只是为了改变些什么。

可是,没有想到,这样持久不断的行为,居然可以让事物改变得这样的深刻和有意义。他已经不仅仅是关于一个人的自我救赎了。它影响了周围的人们,改变了他们的生活,影响了那里的环境,而这影响,让我们震撼和感动。

而当人们在已是满目成林的山谷里感谢自然感谢生活的时候,没有人知道,N年前的这里曾是没有人愿意居住的地方,也不知道这片森林其实是一个人花了大半辈子去呵护的。“天助自助者”,生命的美丽就在于此,你永远不知道曾经的一个小小的决定,只是一个小小的信念,坚持下去就会有美丽的花朵开出。

回想起之前看的动画《老人与海》:“一个人可以被毁灭,但是不可以被打败”——在“牧羊者”中同样可以看到这种精神,其实,上帝给予生命,也给了你自己把握生命如何度过的权利。

有人说,生命的意义就是MAKE A DIFFERENCE.而在我看来,牧羊人的这个DIFFERENCE不算小了。

时间向前,不会停止。不管你愿不愿意,不管遇到多大的挫折和打击,与其趴在地上不愿起来,不如自己跳起,去迎接,找好方向,继续奔跑。这就是积极的心理重建。在牧羊人的一生中,我们看到了生命无限的可能性。 - ()

[The following English translation of Jean Giono's original essay in French by Peter Doyle is a public domain text. For your convenience, we're reproducing it here in it's entirety. Found via the excellent Ming the Mechanic.]

The Man Who Planted Trees

【In order for the character of a human being to reveal truly exceptional qualities, we must have the good fortune to observe its action over a long period of years. If this action is devoid of all selfishness, if the idea that directs it is one of unqualified generosity, if it is absolutely certain that it has not sought recompense anywhere, and if moreover it has left visible marks on the world, then we are unquestionably dealing with an unforgettable character.

About forty years ago I went on a long hike, through hills absolutely unknown to tourists, in that very old region where the Alps penetrate into Provence.

This region is bounded to the south-east and south by the middle course of the Durance, between Sisteron and Mirabeau; to the north by the upper course of the Drôme, from its source down to Die; to the west by the plains of Comtat Venaissin and the outskirts of Mont Ventoux. It includes all the northern part of the Département of Basses-Alpes, the south of Drôme and a little enclave of Vaucluse.

At the time I undertook my long walk through this deserted region, it consisted of barren and monotonous lands, at about 1200 to 1300 meters above sea level. Nothing grew there except wild lavender.】

I was crossing this country at its widest part, and after walking for three days, I found myself in the most complete desolation. I was camped next to the skeleton of an abandoned village. I had used the last of my water the day before and I needed to find more. Even though they were in ruins, these houses all huddled together and looking like an old wasps' nest made me think that there must at one time have been a spring or a well there. There was indeed a spring, but it was dry. The five or six roofless houses, ravaged by sun and wind, and the small chapel with its tumble-down belfry, were arrayed like the houses and chapels of living villages, but all life had disappeared.

It was a beautiful June day with plenty of sun, but on these shelterless lands, high up in the sky, the wind whistled with an unendurable brutality. Its growling in the carcasses of the houses was like that of a wild beast disturbed during its meal.

I had to move my camp. After five hours of walking, I still hadn't found water, and nothing gave me hope of finding any. Everywhere there was the same dryness, the same stiff, woody plants. I thought I saw in the distance a small black silhouette. On a chance I headed towards it. It was a shepherd. Thirty lambs or so were resting near him on the scorching ground.

He gave me a drink from his gourd and a little later he led me to his shepherd's cottage, tucked down in an undulation of the plateau. He drew his water - excellent - from a natural hole, very deep, above which he had installed a rudimentary windlass.

This man spoke little. This is common among those who live alone, but he seemed sure of himself, and confident in this assurance, which seemed remarkable in this land shorn of everything. He lived not in a cabin but in a real house of stone, from the looks of which it was clear that his own labor had restored the ruins he had found on his arrival. His roof was solid and water-tight. The wind struck against the roof tiles with the sound of the sea crashing on the beach.

His household was in order, his dishes washed, his floor swept, his rifle greased; his soup boiled over the fire; I noticed then that he was also freshly shaven, that all his buttons were solidly sewn, and that his clothes were mended with such care as to make the patches invisible.

He shared his soup with me, and when afterwards I offered him my tobacco pouch, he told me that he didn't smoke. His dog, as silent as he, was friendly without being fawning.

It had been agreed immediately that I would pass the night there, the closest village being still more than a day and a half farther on. Furthermore, I understood perfectly well the character of the rare villages of that region. There are four or five of them dispersed far from one another on the flanks of the hills, in groves of white oaks at the very ends of roads passable by carriage. They are inhabited by woodcutters who make charcoal. They are places where the living is poor. The families, pressed together in close quarters by a climate that is exceedingly harsh, in summer as well as in winter, struggle ever more selfishly against each other. Irrational contention grows beyond all bounds, fueled by a continuous struggle to escape from that place. The men carry their charcoal to the cities in their trucks, and then return. The most solid qualities crack under this perpetual Scottish shower. The women stir up bitterness. There is competition over everything, from the sale of charcoal to the benches at church. The virtues fight amongst themselves, the vices fight amongst themselves, and there is a ceaseless general combat between the vices and the virtues. On top of all that, the equally ceaseless wind irritates the nerves. There are epidemics of suicides and numerous cases of insanity, almost always murderous.

The shepherd, who did not smoke, took out a bag and poured a pile of acorns out onto the table. He began to examine them one after another with a great deal of attention, separating the good ones from the bad. I smoked my pipe. I offered to help him, but he told me it was his own business. Indeed, seeing the care that he devoted to this job, I did not insist. This was our whole conversation. When he had in the good pile a fair number of acorns, he counted them out into packets of ten. In doing this he eliminated some more of the acorns, discarding the smaller ones and those that that showed even the slightest crack, for he examined them very closely. When he had before him one hundred perfect acorns he stopped, and we went to bed.

The company of this man brought me a feeling of peace. I asked him the next morning if I might stay and rest the whole day with him. He found that perfectly natural. Or more exactly, he gave me the impression that nothing could disturb him. This rest was not absolutely necessary to me, but I was intrigued and I wanted to find out more about this man. He let out his flock and took them to the pasture. Before leaving, he soaked in a bucket of water the little sack containing the acorns that he had so carefully chosen and counted.

I noted that he carried as a sort of walking stick an iron rod as thick as his thumb and about one and a half meters long. I set off like someone out for a stroll, following a route parallel to his. His sheep pasture lay at the bottom of a small valley. He left his flock in the charge of his dog and climbed up towards the spot where I was standing. I was afraid that he was coming to reproach me for my indiscretion, but not at all : It was his own route and he invited me to come along with him if I had nothing better to do. He continued on another two hundred meters up the hill.

Having arrived at the place he had been heading for, he begin to pound his iron rod into the ground. This made a hole in which he placed an acorn, whereupon he covered over the hole again. He was planting oak trees. I asked him if the land belonged to him. He answered no. Did he know whose land it was? He did not know. He supposed that it was communal land, or perhaps it belonged to someone who did not care about it. He himself did not care to know who the owners were. In this way he planted his one hundred acorns with great care.

After the noon meal, he began once more to pick over his acorns. I must have put enough insistence into my questions, because he answered them. For three years now he had been planting trees in this solitary way. He had planted one hundred thousand. Of these one hundred thousand, twenty thousand had come up. He counted on losing another half of them to rodents and to everything else that is unpredictable in the designs of Providence. That left ten thousand oaks that would grow in this place where before there was nothing.

It was at this moment that I began to wonder about his age. He was clearly more than fifty. Fifty-five, he told me. His name was Elzéard Bouffier. He had owned a farm in the plains, where he lived most of his life. He had lost his only son, and then his wife. He had retired into this solitude, where he took pleasure in living slowly, with his flock of sheep and his dog. He had concluded that this country was dying for lack of trees. He added that, having nothing more important to do, he had resolved to remedy the situation.

Leading as I did at the time a solitary life, despite my youth, I knew how to treat the souls of solitary people with delicacy. Still, I made a mistake. It was precisely my youth that forced me to imagine the future in my own terms, including a certain search for happiness. I told him that in thirty years these ten thousand trees would be magnificent. He replied very simply that, if God gave him life, in thirty years he would have planted so many other trees that these ten thousand would be like a drop of water in the ocean.

He had also begun to study the propagation of beeches. and he had near his house a nursery filled with seedlings grown from beechnuts. His little wards, which he had protected from his sheep by a screen fence, were growing beautifully. He was also considering birches for the valley bottoms where, he told me, moisture lay slumbering just a few meters beneath the surface of the soil.

We parted the next day.

The next year the war of 14 came, in which I was engaged for five years. An infantryman could hardly think about trees. To tell the truth, the whole business hadn't made a very deep impression on me; I took it to be a hobby, like a stamp collection, and forgot about it.

With the war behind me, I found myself with a small demobilization bonus and a great desire to breathe a little pure air. Without any preconceived notion beyond that, I struck out again along the trail through that deserted country.

The land had not changed. Nonetheless, beyond that dead village I perceived in the distance a sort of gray fog that covered the hills like a carpet. Ever since the day before I had been thinking about the shepherd who planted trees. Ten thousand oaks, I had said to myself, must really take up a lot of space.

I had seen too many people die during those five years not to be able to imagine easily the death of Elzéard Bouffier, especially since when a man is twenty he thinks of a man of fifty as an old codger for whom nothing remains but to die. He was not dead. In fact, he was very spry. He had changed his job. He only had four sheep now, but to make up for this he had about a hundred beehives. He had gotten rid of the sheep because they threatened his crop of trees. He told me (as indeed I could see for myself) that the war had not disturbed him at all. He had continued imperturbably with his planting.

The oaks of 1910 were now ten years old and were taller than me and than him. The spectacle was impressive. I was literally speechless and, as he didn't speak himself, we passed the whole day in silence, walking through his forest. It was in three sections, eleven kilometers long overall and, at its widest point, three kilometers wide. When I considered that this had all sprung from the hands and from the soul of this one man - without technical aids - , it struck me that men could be as effective as God in domains other than destruction.

He had followed his idea, and the beeches that reached up to my shoulders and extending as far as the eye could see bore witness to it. The oaks were now good and thick, and had passed the age where they were at the mercy of rodents; as for the designs of Providence, to destroy the work that had been created would henceforth require a cyclone. He showed me admirable stands of birches that dated from five years ago, that is to say from 1915, when I had been fighting at Verdun. He had planted them in the valley bottoms where he had suspected, correctly, that there was water close to the surface. They were as tender as young girls, and very determined.

This creation had the air, moreover, of working by a chain reaction. He had not troubled about it; he went on obstinately with his simple task. But, in going back down to the village, I saw water running in streams that, within living memory, had always been dry. It was the most striking revival that he had shown me. These streams had borne water before, in ancient days. Certain of the sad villages that I spoke of at the beginning of my account had been built on the sites of ancient Gallo-Roman villages, of which there still remained traces; archeologists digging there had found fishhooks in places where in more recent times cisterns were required in order to have a little water.

The wind had also been at work, dispersing certain seeds. As the water reappeared, so too did willows, osiers, meadows, gardens, flowers, and a certain reason to live.

But the transformation had taken place so slowly that it had been taken for granted, without provoking surprise. The hunters who climbed the hills in search of hares or wild boars had noticed the spreading of the little trees, but they set it down to the natural spitefulness of the earth. That is why no one had touched the work of this man. If they had suspected him, they would have tried to thwart him. But he never came under suspicion : Who among the villagers or the administrators would ever have suspected that anyone could show such obstinacy in carrying out this magnificent act of generosity?

Beginning in 1920 I never let more than a year go by without paying a visit to Elzéard Bouffier. I never saw him waver or doubt, though God alone can tell when God's own hand is in a thing! I have said nothing of his disappointments, but you can easily imagine that, for such an accomplishment, it was necessary to conquer adversity; that, to assure the victory of such a passion, it was necessary to fight against despair. One year he had planted ten thousand maples. They all died. The next year,he gave up on maples and went back to beeches, which did even better than the oaks.

To get a true idea of this exceptional character, one must not forget that he worked in total solitude; so total that, toward the end of his life, he lost the habit of talking. Or maybe he just didn't see the need for it.

In 1933 he received the visit of an astonished forest ranger. This functionary ordered him to cease building fires outdoors, for fear of endangering this natural forest. It was the first time, this naive man told him, that a forest had been observed to grow up entirely on its own. At the time of this incident, he was thinking of planting beeches at a spot twelve kilometers from his house. To avoid the coming and going - because at the time he was seventy-five years old - he planned to build a cabin of stone out where he was doing his planting. This he did the next year.

In 1935, a veritable administrative delegation went to examine this « natural forest ». There was an important personage from Waters and Forests, a deputy, and some technicians. Many useless words were spoken. It was decided to do something, but luckily nothing was done, except for one truly useful thing : placing the forest under the protection of the State and forbidding anyone from coming there to make charcoal. For it was impossible not to be taken with the beauty of these young trees in full health. And the forest exercised its seductive powers even on the deputy himself.

I had a friend among the chief foresters who were with the delegation. I explained the mystery to him. One day the next week, we went off together to look for Elzéard Bouffier, We found him hard at work, twenty kilometers away from the place where the inspection had taken place.

This chief forester was not my friend for nothing. He understood the value of things. He knew how to remain silent. I offered up some eggs I had brought with me as a gift. We split our snack three ways, and then passed several hours in mute contemplation of the landscape.

The hillside whence we had come was covered with trees six or seven meters high. I remembered the look of the place in 1913 : a desert... The peaceful and steady labor, the vibrant highland air, his frugality, and above all, the serenity of his soul had given the old man a kind of solemn good health. He was an athlete of God. I asked myself how many hectares he had yet to cover with trees.

Before leaving, my friend made a simple suggestion concerning certain species of trees to which the terrain seemed to be particularly well suited. He was not insistent. « For the very good reason, » he told me afterwards, « that this fellow knows a lot more about this sort of thing than I do. » After another hour of walking, this thought having travelled along with him, he added : "He knows a lot more about this sort of thing than anybody - and he has found a jolly good way of being happy!"

It was thanks to the efforts of this chief forester that the forest was protected, and with it, the happiness of this man. He designated three forest rangers for their protection, and terrorized them to such an extent that they remained indifferent to any jugs of wine that the woodcutters might offer as bribes.

The forest did not run any grave risks except during the war of 1939. Then automobiles were being run on wood alcohol, and there was never enough wood. They began to cut some of the stands of the oaks of 1910, but the trees stood so far from any useful road that the enterprise turned out to be bad from a financial point of view, and was soon abandoned. The shepherd never knew anything about it. He was thirty kilometers away, peacefully continuing his task, as untroubled by the war of 39 as he had been of the war of 14.

I saw Elzéard Bouffier for the last time in June of 1945. He was then eighty-seven years old. I had once more set off along my trail through the wilderness, only to find that now, in spite of the shambles in which the war had left the whole country, there was a motor coach running between the valley of the Durance and the mountain. I set down to this relatively rapid means of transportation the fact that I no longer recognized the landmarks I knew from my earlier visits. It also seemed that the route was taking me through entirely new places. I had to ask the name of a village to be sure that I was indeed passing through that same region, once so ruined and desolate. The coach set me down at Vergons. In 1913, this hamlet of ten or twelve houses had had three inhabitants. They were savages, hating each other, and earning their living by trapping : Physically and morally, they resembled prehistoric men . The nettles devoured the abandoned houses that surrounded them. Their lives were without hope, it was only a matter of waiting for death to come : a situation that hardly predisposes one to virtue.

All that had changed, even to the air itself. In place of the dry, brutal gusts that had greeted me long ago, a gentle breeze whispered to me, bearing sweet odors. A sound like that of running water came from the heights above : It was the sound of the wind in the trees. And most astonishing of all, I heard the sound of real water running into a pool. I saw that they had built a fountain, that it was full of water, and what touched me most, that next to it they had planted a lime-tree that must be at least four years old, already grown thick, an incontestable symbol of resurrection.

Furthermore, Vergons showed the signs of labors for which hope is a requirement : Hope must therefore have returned. They had cleared out the ruins, knocked down the broken walls, and rebuilt five houses. The hamlet now counted twenty-eight inhabitants, including four young families. The new houses, freshly plastered, were surrounded by gardens that bore, mixed in with each other but still carefully laid out, vegetables and flowers, cabbages and rosebushes, leeks and gueules-de-loup, celery and anemones. It was now a place where anyone would be glad to live.

From there I continued on foot. The war from which we had just barely emerged had not permitted life to vanish completely, and now Lazarus was out of his tomb. On the lower flanks of the mountain, I saw small fields of barley and rye; in the bottoms of the narrow valleys, meadowlands were just turning green.

It has taken only the eight years that now separate us from that time for the whole country around there to blossom with splendor and ease. On the site of the ruins I had seen in 1913 there are now well-kept farms, the sign of a happy and comfortable life. The old springs, fed by rain and snow now that are now retained by the forests, have once again begun to flow. The brooks have been channelled. Beside each farm, amid groves of maples, the pools of fountains are bordered by carpets of fresh mint. Little by little, the villages have been rebuilt. Yuppies have come from the plains, where land is expensive, bringing with them youth, movement, and a spirit of adventure. Walking along the roads you will meet men and women in full health, and boys and girls who know how to laugh, and who have regained the taste for the traditional rustic festivals. Counting both the previous inhabitants of the area, now unrecognizable from living in plenty, and the new arrivals, more than ten thousand persons owe their happiness to Elzéard Bouffier.

When I consider that a single man, relying only on his own simple physical and moral resources, was able to transform a desert into this land of Canaan, I am convinced that despite everything, the human condition is truly admirable. But when I take into account the constancy, the greatness of soul, and the selfless dedication that was needed to bring about this transformation, I am filled with an immense respect for this old, uncultured peasant who knew how to bring about a work worthy of God.

Elzéard Bouffier died peacefully in 1947 at the hospice in Banon. - 和我的最爱“Crac!”一样,也是出自加拿大艺术大师Frédéric Back的粉彩动画,是用彩铅和松脂在毛胶片上绘制而成。他的作品,都蕴涵着一种沧桑的历史感,和抒情诗一样的氛围,美到了极致。对我来说最大的遗憾是:影片从头到尾,鸟语般流利的法语旁白就一直没断线,对于我这法语白痴来讲,就只能欣赏画面猜意思,等于是漏掉了二分之一的信息。所以,我还不敢妄言这部动画有多伟大,但是就凭画面,也要先给它四星。