科学怪人的新娘 The Bride of Frankenstein(1935)

又名: 弗兰肯斯坦的新娘

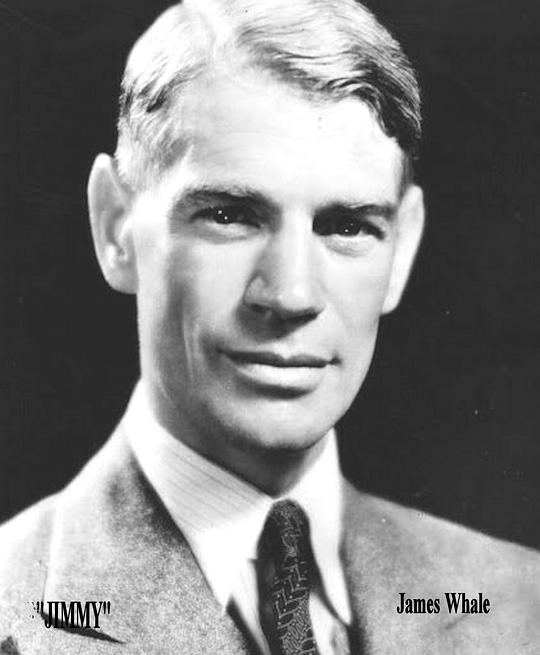

导演: 詹姆斯·惠尔

编剧: 威廉·赫尔伯特 约翰·L·鲍尔德斯顿 Josef Berne Lawrence G. Blochman 罗伯特·弗洛里 菲利普·麦克唐纳 汤姆·里德 R·C·谢里夫 Edmund Pearson Morton Covan

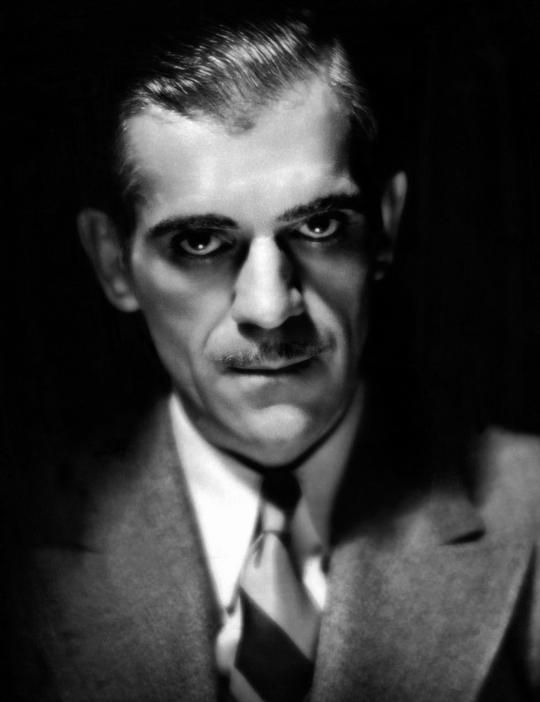

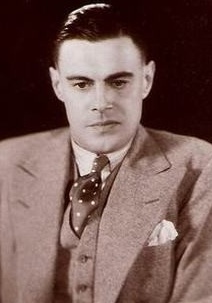

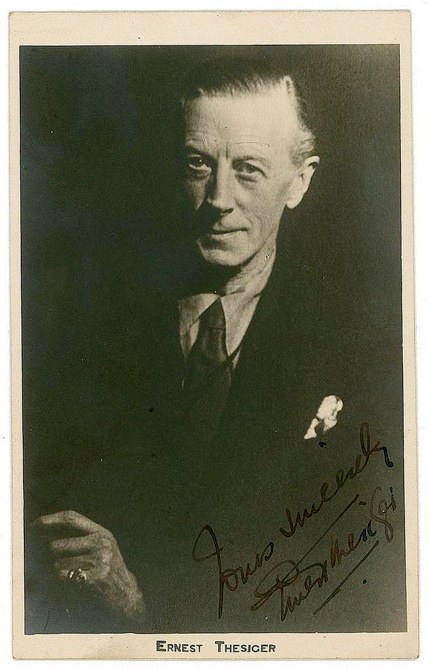

主演: 波利斯·卡洛夫 科林·克利夫 瓦莱莉娅·霍布森 欧内斯特·塞西杰 埃尔莎·兰彻斯特 加文·戈登 道格拉斯·沃尔顿 尤娜·奥康纳 E.E. Clive 卢西恩·普里瓦尔 O·P·赫吉 德怀特·弗莱伊 Reginald Barlow 玛丽·戈登 Anne Darling 泰德·比林斯 Robert Adair 诺曼·安斯利 比利·巴蒂 Frank Benson

制片国家/地区: 美国

上映日期: 1935-04-20(美国)

片长: 75 分钟 IMDb: tt0026138 豆瓣评分:7.7 下载地址:迅雷下载

简介:

- 故事紧接《科学怪人》结尾火烧科学怪人场面,弗兰肯斯坦和他制造的科学怪人都活了下来,科学怪人并没有像博士想象的那样杀死……弗兰肯斯坦决定洗手不干,但另一位疯狂的科学家怪博士找到弗兰肯斯坦要合作造个女人,并绑架他的妻子作为威胁。弗兰肯斯坦只好答应。科学怪人逃生后,历经险阻最终与怪博士相遇,三人在古堡中期待科学怪人的新娘诞生……

演员:

影评:

- 金刚站在帝国大厦的顶端的时候,那些喜欢性和政治的评论家认为他政府了男性世界,而当他怀抱(手捏)

Fay Wray的时候,这个女人则成为他征服的奖励品。这也许是显然的。

《科学怪人的新娘》在类型上超越了前集《科学怪人》,对于四年之后的续集,这是保守判断。四年间,詹姆斯 威尔拍摄了《黑暗古宅》(the old dark house)1932、《隐形人》(the invisible man)1933等影片,风格已经彻底脱离了《科学怪人》一片中的严肃刻板,这也许与他在好莱坞的地位有关,也应当认为是他游刃有余的与审查机构的周旋的映射。1931年环球购买《科学怪人》剧本时,当时是伯德斯顿的剧本,其中已经包含了一个被创造的女恶魔,但是没有被影片采用。

而最后《科学怪人的新娘》的剧本也是数次修改,其中包括女恶魔的身体部件是从何处搜集来的,心脏和大脑的来源,最后选择了威廉 赫尔伯特。

影片的开始是雪莱夫妇和拜伦的谈话,这一段是迫于电影审查的压力而添加的,尤其是雪莱夫人“承认”:这个故事是有关“道德”的。因为只有这样才能避免观众认为电影反映了真实的事件,而非一个传奇的幻想故事。影片中很多修改的原因大多是这个原因,当然,有些没有修改的地方也未必传达了审查机构希望的“那样”。

故事的开始承接《科学怪人》的结尾,弗兰肯斯坦被恶魔(鲍里斯 卡洛夫饰演)从磨房高处扔下来,自己消失在燃烧的磨房中。燃烧的磨房消灭恶魔影响了《范海辛》(式)的电影,而如同本片一样,如此的方法似乎无法毁灭恶魔。恶魔在磨房下的水池中保住了性命。值得一提的是,恶魔绝对不是我们现在能够想象或看到的不可一世的不死怪物,如同金刚一样,你会发问:他也喝水吗?他吃什么东西?他会流血么?答案都是肯定的,本片中恶魔有着一切人的特征,他只是一个力量巨大的人。如同在习惯了好莱坞大片的人看金刚最后“坠入”城市时所感受到的不解,这样一个庞然大物居然就这样死掉了,恶魔带给你的感受似乎时相同的。他被子弹击中后痛苦的表情,被市民围困后捆绑,如果不是超强的力量,他根本无法威胁任何人。

在恶魔被市民追赶的时候,他来到了一个孤独的老人那里,老人双目失明,在寂寞的驱使下与恶魔成为了朋友,关键在于他是一个看不见的人,所有的其他人看到恶魔的反映是恐惧尖叫,唯独他没有,从这个角度看恶魔,其实只是一个长相丑陋的人。人们对他有着自然的排斥,这也导致了他狂暴的伤害那些尖叫的人。老人在恶魔睡觉前感谢上帝赐予他一个朋友,流着眼泪诉说他的寂寞,此时恶魔也流出了泪水。不过这段友谊很快被摧毁,赶来的市民“救走”了老人,恶魔再次逃走,他痛苦的选择了一条“自我毁灭”的道路,钻到墓穴中,人们说他“由死人制造”,所以坟墓是他的归宿。

品尝到“友谊”幸福的恶魔遇到了普特瑞斯教授,当时他正在攫取一个少女的尸体,寻找制造女恶魔的大脑。恶魔希望他能够快点给自己制造一个朋友,并帮助教授胁持了在磨房大火中受伤不愿再制造怪物的弗兰肯斯坦。从语言到感情,恶魔在浩劫中完成了社会化,人的躯壳终于有了人的思想。

最后女恶魔在暴风雨之夜被制造成功,普特瑞斯兴奋的高呼:“The bride of Frankenstein!”,其实这句话并非表达了恶魔的名字叫做弗兰肯斯坦,也不是对弗兰肯斯坦本人发出赞美,原因在于女恶魔的心脏,这颗心脏是弗兰肯斯坦的新婚妻子的心脏,这也是为什么后来女恶魔拒绝了男恶魔的爱而始终依偎在弗兰肯斯坦怀里的原因。但当初审查的时候未能通过,所以改为教授的手下杀害了一名过路女子取得了心脏,弗兰肯斯坦夫妇被恶魔释放。于是出现了“弗兰肯斯坦的新娘”的说法。(威尔似乎在当时还以为心脏是用来思考的器官)

恶魔在被新娘拒绝了后释放了弗兰肯斯坦夫妇,拉下了实验室的一个关键的闸门,与邪恶的普特瑞斯教授和女恶魔一起毁灭在实验室的爆炸中。

在很多《科学怪人》包括对雪莱妇人剧本的分析中认为,弗兰肯斯坦创造了一个活生生的男性恶魔,这对女性在社会中承担的角色构成了侵犯和威胁,创造是一种否定女性生殖的激进方式,而且恶魔来自一个男性科学家的“分娩”。如此一来,女恶魔的创造虽然被女权主义者认为加剧了这种侵犯,但实际上,可以从影片中看到,女恶魔的诞生是为了与男恶魔形成繁殖的对称,这又回到了传统生殖的路子上。不过似乎没有人认为,威尔将《科学怪人》中的思路进行矫正,原因也许在于没有人认为恶魔是人,恶魔之间的交媾繁衍了一个新的种族,这是普特瑞斯教授的主要观点。

如果能够抛开所谓的女权观点来看这部影片,我宁愿认为这是一部边缘人的故事,来自死亡,毁灭于觉醒。詹姆斯 威尔在1935年以公开的同性恋身份生活在好莱坞,即使在今天也是一件十分困难的事情,这个事实决定了他在拍摄科学怪人的时候,将恶魔的受斥形态描述的细致入微,拥有人的躯壳却游离在人群之外,冠以“恶魔”的标签,科学怪人一点点被人同化:渴望友情,心地善良、喜欢杜松子酒和雪茄,然而依然处在人群的追捕中,最后连自己的“同类”:女恶魔都拒绝了自己,这样一种被遗弃的感受让他自己选择了毁灭,同时也毁灭了造成他如此境遇的人——创造者。 弗兰克斯坦的新娘作为科学怪人的续集,给了这个故事一个完整的结尾。故事续接上一部的结尾,众人以为怪物被烧死在磨房,但实际上在那场大火中怪物幸存下来,并经过一系列事件之后被一位孤独的盲人所收留。在这位盲人那里,怪物学会了语言和与他人相处的道理,也明白了自己的不安源自于自己的寂寞。这之后怪物遇见了一位对尸体复活技术狂热的科学家,科学家告诉怪物自己可以为它创造一个“朋友”,但需要弗兰克斯坦的帮助,随后怪物和科学家挟持了弗兰克斯坦的妻子胁迫他一起创造出那位“新娘”。可是这位新娘却同他人一样惧怕怪物,心灰意冷的怪物最后决定放过弗兰克斯坦和他妻子,然后和“新娘”还有科学家同归于尽。

与前作一样,弗兰克斯坦的新娘这个故事的主题同样在讨论人性会如何主导技术的运用,而这种应用又会给人们带来什么样的影响,不同的是各个角色的立场都发生了改变,而且将重点通过男女关系,人与怪物之间的关系而不是创造者和创造物的关系所表现的。而讨论关系时,每个事物都有具像化的代表,这些代表就是电影中每个人物。

所以在下文中我想讨论每个人物和其所在现实中映射的事物。

首先是怪物,与前作不同,前作中它象征的就是技术,完全理性的力量,没有感情的创造物。这部电影中,怪物遇到盲人之前,怪物还是那个代表“技术”,此后怪物了解了自己的恐惧和渴望,并且从盲人那里学会了语言,和与人相处的方法,产生了自己的思想。所以在这部电影后期,怪物的立场就改变了,变成了一个有需求的人,所以在这部电影中,怪物的立场和弗兰克斯坦还有Pretorius博士平行的。电影中期开始,怪物需要消解孤独,这是这种需要导致了新娘的诞生。所以此时的怪物代表着面对问题时人们的需求。

然后是弗兰克斯坦博士和Pretorius博士,两者各象征着科学家的一种心态。弗兰克斯坦博士因为前作中和怪物的冲突,理智的认识到了尸体复活技术潜在的威胁。而Pretorius博士则是一个对技术痴狂的人,他追求一种技术的同时可以无视伦理道德,甚至为了新鲜的器官,不惜指使助手谋杀少女。而结尾的剧情,也隐喻着这种无视伦理的狂热必定会导致狂热者自身的毁灭。而因为妻子被挟持而参与实验的弗兰克斯坦博士则和妻子活着看到这场噩梦结束。

最后是那位被弗兰克斯坦,弗兰克斯坦博士,Pretorius博士共同创造的新娘。虽然她的出场只有三分钟,但无疑是整部电影的焦点。她就相当于前作中的怪物,代表着“技术”。她是怪物为了消解寂寞的工具,是弗兰克斯坦解救妻子的工具,是Pretorius博士向世人别人证明自己成就的工具。初生的她和前作中的怪物一样对任何人都没有恶意,但是同样具有人类的本能。见到怪物后受到惊吓,无疑是导致怪物选择自我毁灭的主要原因,这段情节也寓言着当人们对技术所抱有的期望所破灭的担忧。

总的来说,作为一部早期的科幻电影,这部电影可以说是里程碑式的。这部电影的所讨论的话题是对科学怪人这部电影的话题的辩证和预测。这部电影中用人造怪物代表技术,用人与怪物之间的博弈去喻示人与技术的关系在后来的电影中都有体现。如异形系列,日本动画电影阿吉拉还有各种关于病毒的电影。

中文版:

In the 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein, the sequel to the 1931 film Frankenstein, the Creature, an entity composed of dead bodies by scientist Henry Frankenstein, encounters an elderly, blind male hermit in a hut on the hill (00:34:55-00:44:34). He befriends the Creature and teaches the Creature English (Bride 00:36:40-00:43:15). However when lost villagers come to the hut, they recognize the Creature as the monster in the country (Bride 00:43:15-00:43:57). Eventually, they shoot the Creature, burn the hut down, and purportedly save the blind man from the Creature’s keep (Bride 00:43:59-00:44:34). Why do able-bodied people treat the blind hermit man with kindness and pity while they disrespect and hunt the mute Creature with a monstrous figure of stitches and an abnormal brain in this sequence? To answer it, this essay will analyze the representation of disabilities and queerness in horror films, utilizing research about the novel Frankenstein and works inspired by it including the film series, and introducing crip theory, an intersection of disability studies and queer theory. Through the lens of crip theory, the essay argues that the Creature and the blind hermit man are treated differently, because they fall into two different stereotypical narratives that respectively link disability with inner depravity and angelic morality, and the Creature’s non-binary identity including but not limited to gender challenges heteronormativity.

In Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, Robert McRuer introduces crip theory that connects disability studies and queer theory with the shared pathologized history and the silent unspoken categories of normality in both cases, ability and heterosexuality (McRuer 1). The unspoken categories interweave with each other, generating the compulsory able-bodied heteronormativity (McRuer 1). Able-bodiedness, “the opposite of disability” in the dictionary, refers to a compulsory concept “in the emergent industrial capitalist system” that considers one’s flexibility in work as a norm (McRuer 7-8, 16). Heteronormativity refers to the compulsory assumption that “nearly everyone” should be in the so-called “normal relations of the sexes” that require consistency in sex and gender, known as cisgender, and the pursuit of the opposite sex, known as heterosexual (McRuer 8-9). In this essay, queer/queerness is used as an umbrella word that refers to all identities, communities, and concepts that are not heterosexual or cisgender. As a result, these two categories produce disability and queerness respectively yet mutually. In the films, the Creature is disabled and non-binary disrupting the able cis-hetero norms in every facet.

The Creature is represented as disabled in various respects such as cognitive disability, skin disorders, and muteness through makeup design and the narrative. In the first film, the brain is literally labeled as “abnormal” for its degeneration causing the original owner’s violent brutality according to the medical professor (Frankenstein 00:07:19-00:07:45). In Frankenflicks: Medical Monsters in Classic Horror Films, Stephaine Brown Clark, Professor Emerita in the Department of Health Humanities and Bioethics at the University of Rochester, points out that the makeup design of the Creature’s scar on the skull visually cues people to the abnormal brain inside, the pieced-together body and their disability (Clark 136-137). The Creature’s stitched-togetherness furthers visible physical disabilities (Clark 137).1 When the blind feels the stitches as he invites the Creature into the hut through physical interactions, he states, “You are hurt, my friend”, acknowledging the Creature’s skin deformity (Bride 00:37:28-00:37:35). Additionally, the Creature’s muteness is another sign of disability. After the physical interactions, the hermit asks about the Creature’s name only to receive noises rather than utterances in reply (Bride 00:38:00-00:38:12). He sighs, “Perhaps you are afflicted too. I cannot see and you cannot speak”, implying that muteness is similar to blindness in disability (Bride 00:38:15-00:38:23).

The blind’s resonation with the Creature, in dialogue as well as mise-en-scene, proposes the Creature’s disability in a general sense, particularly the unifying sentiment of isolation among the disabled community. For the purposes of this essay, disability will be defined under the parameters of (in)visibility, as is commonly seen in crip theory. To think about the non-normative identity, one must think in line with the politics of visibility (McRuer 2). Media Arts scholar Travis Sutton identifies one of the common stereotypical representations of disabled people as isolated from able-bodied people and each other in both narrative and frame in Avenging the Body: Disability in the Horror Film (76). The sequence starts with a long shot of the Creature climbing up the hill to approach the hut where the diegetic music comes from (Bride 00:35:15-00:35:30). The mise-en-scene underscores the distance of the uncultivated hill where the hut is located, revealing the isolation of the two from able-bodied people. The desolation is directly stressed in the line of the hut’s owner, let alone in the film credits where the elderly blind man is dubbed the uniquely fitting title of “Hermit”, “It’s very lonely here, and it’s been a long time since any human being came into this hut” (Bride 00:39:09-00:39:15, 01:14:14). In another long shot, the blind man inside plays the violin alone while the Creature looks through the window to observe the hut's interior (Bride 00:35:26). The Creature’s head is positioned solely in the tiny window frame. With one inside and the other outside individually, the scene depicts the two disabled characters separated from each other, whereas the able-bodied villagers debut as a pair (Bride 00:43:15). Hence the hermit thanks God for bringing “lonely children together”, again implying their shared disability (Bride 00:39:52-00:40:15). The man and the Creature are socially rendered undesirable, and therefore invisible, literally alone in the woods.

Although both the Creature and the hermit are portrayed as lonely disabled characters, they fall into two different stereotypes of disabled characters that tie disability to inner depravity and angelic morality respectively. The Creature’s disability is associated with inner depravity. In the film, the professor in the medical school teaches Frankenstein that “only evil can come from” a criminal’s abnormal brain (Frankenstein 00:29:56-00:29:58). From the professor’s institutional scientific judgment, the brain is abnormal so a creature with the brain will be evil. The underlying meaning of this claim is the equivalence of the psyche and brain failing to distinguish their independence from each other (Clark 135). Furthermore, the monster’s piece-together body is deployed to infer the monster’s soul “lacking the unity of composition that marks it as beautiful” (Clark 137). On the other hand, the blind elder is prominently shown as Saintly Sage. Saintly Sage is usually an old character whose disability, mostly blindness, “allegedly grants this character access to higher levels of wisdom, foresight, and morality” (Sutton 78). In the film, blindness prevents him from seeing the monstrosity of the Creature, contributing to his realization of their communal loneliness, so he feels for, accommodates, and makes friends with the Creature (Sutton 78-79). The stereotypes are presented to the audience as well as to the villagers. The villagers are surprised that the hermit introduces the Creature as his friend, exclaiming, “Friend? This is the fiend that’s been murdering half the countryside. Good heavens, man, can’t you see? Oh, he’s blind” (Bride 00:43:45-00:43:52). At last, they perceive the man’s visual impairment directly, indirectly cognizing the Creature’s disability and in effect monstrifying it. The able-bodied people admit the mutual disability of the Creature and the hermit while segregating them from each other by stereotypical narratives.

All disability stereotypes should be criticized because they objectify disabled people and deny their full moral agency. The distance and isolation are stereotypically exhibited due to the discomfort and intrigue raised in able-bodied people when they encounter disability (Sutton 76). Specifically for the intrigue, it leads to able-bodied people’s objectification of disability as spectacles (Sutton 76). Viewed as innocent sages, the characters are denied any other desires than the hope of collective support within the disabled community and protection from abled-bodied people (Sutton 78). In the film, the blind hermit is simply portrayed as a giver to the Creature craving for a reciprocal companion and an inferior rescued by the able-bodied villagers. On the other hand, if viewed as monsters, their morality and souls are constrained by their appearance. In other words, their souls are cracked and trapped in their broken bodies. In the films, able-bodied people monstrify the Creature for the image, namely stitches and cognitive disability. In this comparison, disabled people are superficially ranked for different types of disability. In plain words, they are either extremely good because of their physical disability or extremely bad on account of their mental and cognitive disability. Characterized as one of two moral extremes, they are objectified by virtue of their divergence to normativity and denied the complexity of character and the character arc permitted of able-bodied individuals.

Besides the transgression in the able/disabled binary, the Creature has a non-binary identity including but not limited to gender, such as life/death and human/non-human. American academic Jack Halberstam introduces the term trans* in Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability “unfolding categories of being organized around but not confined to forms of gender variance” (4). The “asterisk modifies the meaning of transitivity by refusing to situate transition in relation to a destination, a final form, a specific shape, or an established configuration of desire and identity” (Halberstam 4). Concerning gender, for instance, it means that being trans* rejects a transition that aims to end up in the existing male/female gender model. Trans* is used as an umbrella word that covers all non-cisgender identities, including but not limited to transgender and non-binary (Halberstam 1, 5).2 Along the “non-telic definitional lines” of Halberstam’s trans*, Chris Washington, associate professor of English at Francis Marion University, contends the non-binary identity of the Creature in Non-Binary Frankenstein? (71).3 Especially, the ontology of the Creature’s identity is trans* that escalates and is escalating without “any telos or desire for telos” (Washington 71). Thus, it is improper to impose a binary on the non-binary with(out) a meta-dichotomy of binary/non-binary.

Many seemingly paradoxical lines in the films insinuate the concession of the human characters on the Creature’s non-binary identity. In Frankenstein (1931), the scientist recommends his experiment as the “brain of a dead man to live again” in the body he made from corpses while he affirms that the “body is not dead” given that “it has never lived” (00:16:11-00:16:18, 00:22:09-00:22:13). The underlying meaning of the two lines is that the Creature is not simply a living collage of dead tissues. To put it another way, the goal of the experiment then blurs the inherent existence of the border in bilateral life-death relations. Moreover, the argument that the body made from cadavers is not dead for the absence of living beforehand illustrates Frankenstein’s non-binary recognition of life/death in his project. As Washington analyzes, the Creature is “created from bits and pieces of the living and the dead and the human and nonhuman, merging what cannot be merged into a blurring of non-binaristic boundaries” (69). In the sequel, the scientist revisits his plan “to create a man” remarking that he “could have bred a [new] race” (Bride 00:13:34-00:13:51). A race commonly refers to a species that is other than the human form that man refers to. The retrospective commentary also suggests that Frankenstein senses the Creature outsteps the human/non-human binary. Reintroducing the lines of the villagers, “he isn’t human. Frankenstein made him out of dead bodies”, we can draw a similar inference (Bride 00:43:53-00:43:57). They realize that the Creature is a presence that transcends the binary logic. Therefore, the Creature is ontologically ambiguous without an end considering that the cis-hetero normative framework is insufficient for it.

The Creature carries a non-binary in both sex and gender, concepts dictated to it by human society because the Creature does not fit into the ideology of the heteronormative society by birth. Resulting in “a species of one”, the origin of the Creature is not a result of a two-sex union but one male instead, which already challenges the cis-hetero fantasy (Washington 68, 80). In Non-Binary Frankenstein?, the author again contends the Creature as

a monster, according to its very (no)name, has no gender, has no name, and is simply something unfathomable, a namelessness that can never be named since naming it would mean it was no longer a monster but something more recognizably like a person complete with a gender identity normatively implied by whatever signifying name it takes. (Washington 66)

This statement on the Creature’s lack of identity ontologically supplements the non-binary gender identity without a telos with the absence of an arche, an originary point. By arguing this, Washington alludes to the deficit of a starting point, namely sex, to the Creature’s sex/gender. It is parallel to the trans* rejection of an established gender “destination” within the Creature non-binary covered in the previous context (Halberstam 4; Washington 71). That is, transgender, conventionally referring to people whose gender identity differs from their assigned sex, should have a (binary) sex allocated first to be deviant from but the Creature being “a species of one” is a creature without assigned sex, a species of androgyny. Thereefore, the Creature disrupts the sex-gender dualism. As an epicene species without binary sex designated to begin with, the Creature’s next request for a female companion is to appropriate the civilized two-sex norm and gender identity in human society.

The divergence between humans and the Creature in the intentions to create a bride demonstrates the conflicts between the Creature’s non-binary and socially structured heteronormativity.4 Doctor Pretorius articulates that his potential innovation of a feminine creature “follow[s] the lead of nature” of the male-female norm to “multiply” and completes the dream of “a man-made race” that is “only half realized” (Bride 00:24:50-00:25:08). In the doctor’s heteronormative assertion, the presence of a female is to fulfill the reproduction function of a species. However, the Creature’s demand for a female is for the sake of companionship. Acculturated by the blind hermit, the Creature enunciates word by word, “Alone. Bad. Friend. Good” (Bride 00:42:00-00:42:10). Later, learning that Doctor Pretorius makes “woman, a friend of [the Creature]”, the Creature says “Woman? Friend. Yes. I want friend. Like me” (Bride 00:50:05-00:50:24). The creature wishes for a woman to resemble the friendship he once had. It is a pursuit for companionship not for the reproductive norm in heteronormativity.

The Creature unites disability with queerness as crip theory does. In the films, the Creature’s disabled body stitched up with dead tissues causes the non-binary identity to transpire. Inversely, the non-binary identity, especially life/death with the dead criminal’s abnormal brain, also influences the disability of the Creature. Rather, the villagers’ saying “Good heavens, man, can’t you see?” in a dismissive tone are ramified by the compulsory able-bodied heteronormativity for the presumption that the hermit is male and he should be able to see (Bride 00:43:48-00:43:50). However, the Creature outgrows the ideology of normalcy constitutionally.

By criticizing the norms, crip theory extends beyond the bounds of the disabled and queer community, engaging everyone in all periods and regions, so as the Creature. For instance, McRuer reminds people that “everyone is virtually disabled, both in the sense that able-bodied norms are ‘intrinsically impossible to embody’ fully and in the sense that able-bodied status is always temporary, disability being the one identity category that all people will embody if they live long enough” (McRuer 30). In other terms, crip theory advocates that we are all disabled to a certain degree both in the manner that we could never fulfill the abled-bodied ideal fully and disability could befall anyone anywhere at any time. The Creature deepens the doubt on normative standards. Being a non-binary disabled figure, it transgressively queers everyone. For example, since fear usually relates to feminity, the visually-abled cishet-men’s fright as they meet the Creature contends with their manhood, shedding light on their womanhood. It reveals the co-existence of masculinity and femininity in everyone like the co-existence of androgen and estrogen. There is always a part of us that is not manly or womanly. On that account, able-bodied heteronormativity is a myth that no one can achieve completely. Given the oxymoron of impossible perfection, is everyone then disabled and queer to some extent?

Notes

1Even though Clark states that it was Kenneth Branagh who emphasized the creature’s skin in his film Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1996) as opposed to the emphasis on the skull in the 1930s series, the stitches in Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein as part of the makeup design are recognizable visually even if that is not the main focus of the makeup design (Clark 137). Therefore, the analysis of the stitches in the 1996 version could be translated to the 1930s series.

2This essay acknowledges that there are differences between transgender and non-binary identities. While arguing the Creature transcends all kinds of sex and gender norms, for the purpose of this essay the terms can be used interchangeably.

3The article focused on the body in Mary Shelley’s novel instead of the film series and engaged it with transgender and trans* theory. The analysis is mostly concentrated on how the creature is created and exists. Since the origin story of the Creature in the films is similar to that in the novel, the analysis could be appropriated with the shared setting of “a monster created from cadavers out of rifled graves” (Bride 00:03:20-00:03:23).

4The assumption that only cisgender males can have a bride is an obvious example of heteronormativity— assuming people’s gender by the partner— as anyone with any gender identity can have a bride as long as their partner’s gender is female. Identity is not, or at least not only, constructed by others’ perceptions or assumptions. It should take the self-awareness of the subject into account. Not to mention that it is dubious about the idea of treating the Creature’s Bride as female, similar to identifying the Creature as male.

Works Cited

Bride of Frankenstein. Directed by James Whale, performances by Boris Karloff, Colin Clive, Valerie Hobson, Elsa Lanchester, and Ernest Thesiger, Universal Pictures, 1935.

Clark, Stephanie. “Frankenflicks: Medical Monsters in Classic Horror Films.” Cultural Sutures: Medicine and Media, edited by Lester D. Friedman, Duke University Press, 2004, pp. 129-148.

Frankenstein. Directed by James Whale, performances by Colin Clive, Mae Clarke, John Boles, Boris Karloff, and Dwight Frye, Universal Pictures, 1931.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability, University of California Press, 2018.

McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, New York University Press, 2006.

Sutton, Travis. “Avenging the Body: Disability in the Horror Film.” A Companion to the Horror Film, edited by Harry M. Benshoff, John Wiley & Sons, 2014, pp. 73-89.

Washington, Chris. “Non-Binary Frankenstein?.” Frankenstein in Theory: A Critical Anatomy, edited by Orrin N. C. Wang, Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2021, pp. 65-83.

本文原为2023秋季学期《人文视野:动物与机器(人)》的期末小论文。由于平台限制,部分内容或许不符格式规范,还望海涵。

- 人造人意味着惩罚

《科学怪人的新娘》中盲眼牧师把科学怪人当作他多年虔诚信教,上帝赐予他的礼物,但讽刺的是,上帝赐予这个虔诚信徒的却是一个人造人,这两个真正能够互相倾听的“Friends”都是被上帝抛弃的子民,

牧师教会了弗郎克斯坦“GOOD”,可是仔细观察会发现弗郎克斯坦学会的东西却是“七宗罪”:

骄傲

贪婪

好色

愤怒

贪食

妒忌

懒惰

弗郎克斯坦对这些贪欲用丑陋的嘴不断“GOOD......GOOD......”相反没有引起我的任何反感,因为“GOOD...... GOOD......”意味着他人的认同,他得到快感的方式并不是欲念的满足,而是他念诵这个词语时心理上得到的满足。他如此低等的满足感却能让人反思 GOOD这个词的原本意义就是“七宗罪”带给人的快感,弗郎克斯坦的GOOD已经超越了“七宗罪”,它直指人类给他带来的心理上的孤寂,远远无法用“七宗罪”的快感来弥补。

这一段是这部片子最好的部分,我甚至觉得它通过一种“俗气”的视觉表达方式取得了高于某些文艺片和实验片的价值,这也是CULT片吸引我的地方。

CULT片的文化就是邪恶宗教文化,CULT的字面意义就是信徒。

僵尸的传统就是WOODOO教(女巫教)的传说,各种CULT怪兽也都是不符合上帝法则的生物,人造人更与科学无关,因为从死人身上复活的生命必然会引起上帝的愤怒。